Camus – De Pest

Aan het laden…

Aan het laden…

Articles

The Plague & The Plague

Dylan Daniel finds many contemporary resonances in Albert Camus’ novel.

Many popular reading lists for the COVID-19 pandemic include The Plague, a 1947 novel by Albert Camus. The author was an existentialist philosopher who was also a journalist, a writer, and a member of the French Resistance to the Nazi occupation. Camus was born in Algeria, and his father died soon after his birth. For a fascinating glimpse into Camus’ life, have a look at Albert Camus: A Biography, by Herbert R. Lottman.

Though he disavowed being called an existentialist as a means to avoid association with Jean-Paul Sartre, a one-time friend turned enemy, Camus’ work nevertheless centers upon existentialist themes, such as each person’s need to take responsibility for their own choices and actions and in doing so to create meaning for their lives. For the existentialists there is no yardstick by which to measure meaning; rather human beings ascribe meaning to life themselves. Camus’ unique twist on this involves couching it within ‘the absurd’. For Camus, we must take responsibility for creating meaning for ourselves just because of the fundamental absurdity of life – the mismatch between what we would want from life and what it actually gives us. And perhaps the most absurd part of the entire affair is that we never find out if we did it right or not. In The Plague living virtuously is presented as one way of creating meaning. But for Camus, even virtue is not meaningful beyond what it means to the one who has it.

In The Plague, the need for the individual to confront the absurd stands out in stark relief, masterfully woven into a fictional narrative of a cholera outbreak which many interpret as an allegory for the Occupation of France during World War II. The first sense of ‘plague’ in the text is literal – a disastrous epidemic which ravages of the town of Oran in Algeria, so that it must be strictly quarantined. However, the second sense in which the term is employed in the novel is more striking, and more enduring. It stands for a decadence of culture which has led Oran into a currency-fixated complacency, especially with respect to the fragility of the relationship between humanity and nature. This complacency results in a lack of vigilance and a resulting inability to mount adequate defenses against the outbreak, which ultimately, tragically, claims the lives of far too many of the town’s citizens. It’s possible to read the book in such a way as to ascribe the outbreak of plague in the first sense to the prevalence of the plague in the second sense.

2020 will forever be known as the year of COVID-19. Politically, I think it will also be remembered as the year in which authoritarian regimes around the world made public their inadequacy. And for too many of us, it will also be remembered as the year in which our own elected officials were too slow to act to prevent the loss of a loved one. Our societies too had become somewhat complacent; the effects of that complacency have been painful. However, as Camus might remind us, all is not lost. We have united in the face of the tragedy, and many people have become better than they were before, setting aside narrow selfish concerns to donate personnel protective equipment to hospitals, care for each other, and stay home to avoid transmitting the disease. This is only one way in which Camus’ novel has resonance for us now.

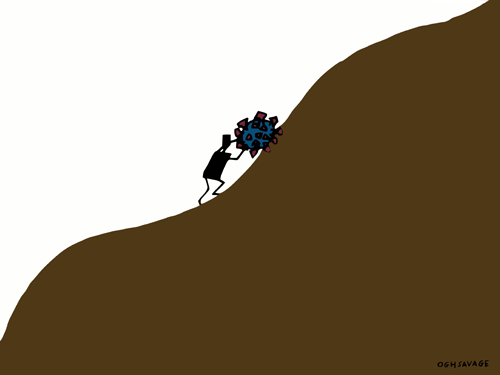

COVID Sisyphus © Owen Savage 2020. Instagram @oghsavage

The Hero

The volunteer Jean Tarrou is perhaps the most striking, the most beautiful, the most admirable character in The Plague. Despite being a stranger visiting town and despite his lack of professional medical training, he sees what needs to be done, and he does it. Tarrou is unable to turn the tide of the plague, and he is unable to save the lives of many people affected by it; but still he stands, stalwart, unyielding, convinced of the rightness of his actions, willing to risk death to save others. In fact, the risks add up as he works, and he does eventually die from the plague, becoming the epidemic’s last victim.

Tarrou’s long soliloquy toward the end of the book is perhaps the most brilliant moment in this extraordinary work. The purpose of this speech is to describe what a close reader might call the ‘real’ plague which is the subtext of the book – the instinct to kill another human being, or at least the tendency to bring about their death by action or inaction. Some people don’t know they have it, this monster lurking within. Others have learned to live with it. For Camus, it would seem, the only path to goodness is to become a third type of person – the type of person Tarrou is: someone who becomes self-aware and works to change himself by helping others. Tarrou knows he is stricken, and seeks to alter himself.

The philosophical history of the idea that we need to improve ourselves goes at least back to ancient Greece. For instance, in his dialogue Gorgias, Plato recounts an argument in which the great founding father of Western philosophy, his teacher Socrates, argues that the purpose of punishment is to make the punished better; hence, if one acts unjustly, it is in one’s own interest to turn oneself over to the authorities for punishment, in order to become better. Camus’ character similarily seeks to work against himself to stamp out any tendency to abandon those who need his help. In so doing, he cultivates his compassion for his fellow man, and so his own humanity. This leads him to create sanitary squads to help mitigate the spread of the disease, to whatever extent possible. The good man, for Tarrou, is “the man who infects hardly anyone, is the man who has the fewest lapses of attention.” Tarrou’s final days are “spent keeping that endless watch upon [himself] lest in a careless moment [he] should breathe in somebody’s face and fasten the infection upon him.”

But the most profound significance of this character in a book about the absurd nature of suffering and the human condition at large, ultimately seems to be as a critique of the way in which good people are used up by the rest of humanity. Tarrou’s sacrifice is in some sense necessitated by the politically-led desire to avoid a ‘false’ alarm at the outset of the disease, even though it is obvious enough to Dr Rieux and other experts what the cause of the increasing death toll is. Yet things have not yet become quite pressing enough to call the politicians to action to prevent things from spiralling out of control.

The Victims

Oran begins the novel in something of a trance. Mundane concerns have overtaken it, and the desire simply to make money has overpowered the desire to utilize that money for good. But money is only good insofar as someone is willing to trade something good for it. Once this is forgotten, avarice – the desire to accumulate wealth for its own sake – is the only possible outcome.

Perhaps the most absurd observation I can make from my reading of the book, is the sense in which for the city the plague is in fact the cure. That is to say, although it kills too many and causes too much grief, the cholera outbreak also breaks down the immoral conditions in which the inhabitants of the town lived before it struck. It brings solidarity, community and meaning back into focus in their lives. The plague also finally holds the politicians to account. The reluctance with which precautionary measures are taken up is woefully indicative of the inadequacy of the machinery of the state to act upon the basis of unfamiliar evidence to bring into effect measures which might have prevented the outbreak. For the inhabitants of Oran, therefore, it is thus both necessary that the plague strike and establish itself among them before anything is done about it, and terrible that there was not more readiness upon the part of the government to act upon the early warning signs recognized by the experts.

We ought not to forget that the culture of the town itself is what drives things in this direction: the citizens are unaware that a plague is possible, being preoccupied with money. Their lack of vigilance ultimately leads to destruction and grief. As Camus says in just the third paragraph of the book:

“Perhaps the easiest way of making a town’s acquaintance is to ascertain how the people in it work, how they love, and how they die. In our little town (is this, one wonders, an effect of the climate?) all three are done on much the same lines, with the same feverish yet casual air. The truth is that everyone is bored, and devotes himself to cultivating habits. Our citizens work hard, but solely with the object of getting rich. Their chief interest is in commerce, and their chief aim in life is, as they call it, ‘doing business’. Naturally they don’t eschew such simpler pleasures as love-making, seabathing, going to the pictures. But, very sensibly, they reserve these pastimes for Saturday afternoons and Sundays and employ the rest of the week in making money, as much as possible.”

Hardly innocent, then. Rather, the citizens of Oran have become complacent. If this sounds familiar, perhaps you are in the type of audience for whom Camus wrote the book.

The Observer

Benjamin Rieux, the doctor tasked by the city government with responding to the plague, is a character initially familiar to anyone who has been watching the news recently. A stalwart man, he is capable of enduring a great deal, and is quite used to administrators who fail to heed his concerns.

Dr Camus diagnosing the human condition

Despite these qualities Rieux is not, for Camus, a virtuous person, for he is not angry enough with the bureaucratic system to force the rapid measures needed. The only hero of The Plague is Tarrou, who does what must be done although he is unqualified and not responsible for the catastrophe of which he becomes a victim. By contrast, Rieux is part of the city’s establishment. Although capable of reflection, of self-awareness, of deep thought, and of friendship, Rieux is more a symptom of the plague than he is a cure for it. As mentioned, the bulk of the population of Oran is primarily concerned with making money and though many commentators are inclined to exempt Rieux from this description, there are reasons to think otherwise – including his final exchange with his wife, in which they talk about the expense of the train ride she is to take.

Although it is present all along in his choice of Rieux as narrator, Camus’ compassion is most clearly visible at the end of the novel. Rieux’s guilt at his recognition that he failed to act strongly enough early on does not diminish his humanity but brings it out. In fact, Rieux approaches wisdom as the work concludes – providing evidence of growth, of a true character arc. Becoming something of a hero himself, Rieux has learned at the close of the work that “joy is always imperiled.” In this simple statement Camus illuminates for us the beauty in the absurd existence of human beings. We continuously make predictions about the future to guide our actions, yet it is often only through tragedy that we learn where the danger really lies. The powerlessness of Rieux is shown through his inability to act at the administrative level early in the story; and it comes full circle as his awareness is expanded at the end of it. What could be more absurd than becoming aware of the danger of a crisis only by living through it, as though it were predestined to happen and nothing one does could change that? In this sense, The Plague allegory suggests that it is the inertia of culture, its prevailing assumption that the future will resemble the past (which David Hume grandly called the ‘Principle of the Universality of Nature’) that makes life absurd.

Hope For The Future

Although it is impossible to truly, absolutely, hope; that is, to ever hope to overcome the absurdity of the human condition, especially as mediated by cultural inertia, there is nonetheless a sort of bastard hope which arises as we confront other fundamental facts of life. It drives our thinking into unfamiliar territory if, for example, we are completely dominated by love of a person (or of anything else). Forced to depart from familiar terrain by the plague, the character Rambert has the epiphany that there is more to the world – more to life, perhaps – than his obsession, than his beloved. And in the face of this epiphany, what is he to do when he is reunited with her? As Rieux ably narrates: “The plague had forced on him a detachment which, try as he might, he couldn’t think away, and which like a formless fear haunted his mind. Almost he thought the plague had ended too abruptly, he hadn’t had time to pull himself together.” The unreadiness of Rambert to confront his love after the plague has ended is a symptom of his realization that the obsession for her which once motivated him is now tempered by an understanding of the absurdity of the world – a world which would not hesitate to see the two of them ripped apart any more than it exercised its sheer caprice in bringing them together.

In essence, The Plague was written to teach us to treasure the moments of happiness and joy we share, just because humanity is, absurdly, ridiculously, painfully inadequately equipped to cope with stressors and stimuli it encounters. How could it not be so? The passing of time dulls our attention to detail, and despite the power of our civilization, the mass of humanity remains slow to respond to threats. The quintessence of the absurdity of existence for Camus in The Plague – just as it is for us reacting to our current plague – is that individuals die when the collective fails to recognize or respond adequately to foreseeable threats. So, as predicted by the narrator of The Plague, ‘the plague’ is not over and will likely never be over. We can only hope and love and act, and be as good as we can be. Yet it is no more right to say that we deserve our fate (as Father Paneloux would have it), than it’s correct to assume that one day the mass of humanity will be able to respond to all threats to it without loss of life. And insofar as we continue to live unawares in the midst of this conflict between our species and nature, life and death will continue to be dictated by means beyond our control, even our understanding. That is to say, life will remain absurd.

© Dylan Daniel 2020

Thomas Dylan Daniel is the author of four books of philosophy, fiction and poetry. www.thomasdylandanielauthor.com

The Plague & The Plague | Issue 138 | Philosophy Now